I first became interested in children's books as a child and particularly as an only child growing up largely in the company of indulgent adults. Books were a way of escaping from having to spend too much time talking to grown-ups, and a way of interacting with all things imaginative and of interest to children.

Early favourites were Just So Stories and in particular The Elephant's Child. I can still hear my father rolling his "Rs" dramatically: "Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees, and find out" as he read the story over and over to me at bedtime. Children love repetition. Other first loves were Wind in The Willows, Noddy, Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass (I can still recite Jabberwocky without prompts), Hilaire Belloc's Cautionary Verses and the wonderful, creepily illustrated National Nursery Rhymes for which the Dalziel brothers provided illustrations that became the stuff of nightmares for me. In particular the engraving of The Spider and the Fly...

They do say that the best gift one can give a child educationally is to read aloud to the child, and I would definitely second that premise. Of course time went on, and I learned to read by myself.

The family moved down to the Sussex coast in order to escape the constant coughs and colds exacerbated by the poor air quality in 1960s London. I was in seventh heaven, I got to live right by the sea, all year round. We moved down in the winter of 1963 and I was amazed to find that the sea was frozen in parts and there were icicles on the breakwaters. There was something quite magical about our village. It was all very neat and tidy, with shops, a duck pond, and lots of thatched roofs. What I didn't realise at the time was that it was "fake" in the sense that it had been built entirely in the 1930s, as a 'Garden Village'; the original village had been subsumed by the sea back in Victorian times.

You could see traces of the old village when the tide went out, and this added to the strangeness and magical atmosphere of the place. It was not long before I discovered Enid Blyton's books for older children, which I consumed with a vengeance. Inspired by Enid, a small gang of us would go on endless expeditions through people's back gardens, village ditches, farmer's yards, always hoping we would find treasure or a mystery to solve. We did unearth a wooden crate once, which held out hope, but it was empty.

Enid Blyton and other authors such as Edith Nesbit, Eve Garnett, C.S. Lewis, P.L. Travers and Mary Norton, continued to inspire, educate and spike my imagination until I came down to earth with a bump. Blyton's Malory Towers and St. Clare's school series were favourites and I could not wait to go off to boarding school as a result of reading these. However, I soon realised that the real thing was a bit more challenging than Blyton had portrayed. I don't think Blyton herself ever went away to school so there were lots of aspects of boarding school life of which she knew very little. Suffice it to say that I never read any more school stories from that point onwards.

Childish books were left behind, then, but never completely. I kept as many of my books as I could for as long as I could protect them from my mother's tidying instincts. She threw away dust jackets with gay abandon because "we don't want the place looking like a bookshop, do we dear?". Later in life, when I became a bookseller, she would ask "haven't you got enough books now, dear?". She never really got it, bless her.

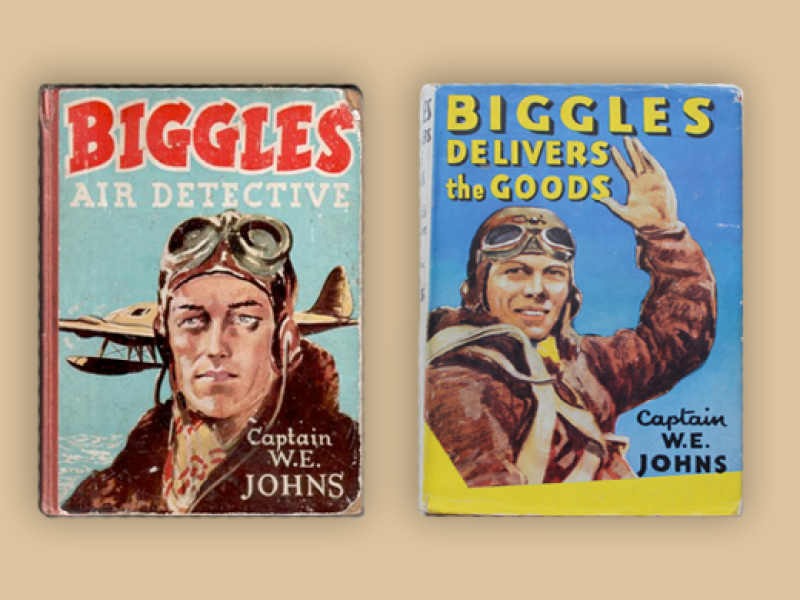

So, I think it was always in the stars that I would become a bookseller, mainly specialising in children's books. The feel, the smell and the look of them is Proustian and the quality and range of material available for a collector is huge. Over 30 years, the way people collect children's books has changed. Today you would not find that many collectors who would try to amass All 800 plus books written by Enid Blyton, they would rather just go for the more obvious series, Famous Five, Secret Seven etc. This is the case with other authors as well, which is a shame as the appeal of collecting becomes more aesthetic and less academic.

Obviously, a lot of this is probably to do with the rising prices of first editions and copies of books in pristine condition, coupled with the fact that many people live in much smaller houses these days, where space for books is definitely at a premium. However, the love for the printed, physical object prevails and many books continue to outlive their makers and owners for hundreds of years. Long may that continue.

This article appears courtesy of Sarah Key. It was originally published on the website of the Provincial Booksellers Fairs Association (PBFA).